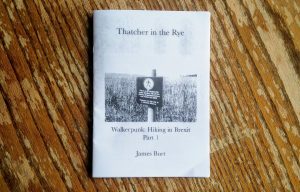

I’m currently putting together a new zine about Brexit and hiking, this time focussing on Daniel Hannan. It includes an account of a hike taken by Chris Parkinson and I. A weird moment on this hike got us thinking about the strange link between Daniel Hannan and Albert Speer.

Speer was Hitler’s architect and, later, the Minister of Armaments for the Third Reich. He stood trial at Nuremberg and was spared a death sentence after persuading the court that he had no knowledge of the Final Solution. So, one link between the two is that they were both part of racist movements but claimed to have no involvement with the racist bits. (Speer went to great effort to argue that he had not been present for Himmler’s speech at the 1943 Posen conference. Hannan went as far as writing an entire book on Brexit that doesn’t mention immigration to provide an alibi for his involvement in the leave campaign.)

The main link between the two is imaginary walks. Hannan is famous for faking a hike in the English countryside. He shared a photograph on social media of a walk near his home, which turned out to have been taken in Wales twenty years before. Speer devoted eleven years of his life to an imaginary journey.

In October 1946, Speer was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment. Long term confinement places a strain on mental health and, in the ninth year of his sentence, Speer decided on a project to keep himself sane. He started out by measuring the 270 meter distance around the prison garden, which he was allowed to stroll each day. He then began to walk 7km a day, mapping the walk onto the journey from his cell to Heidelberg, a distance of 620 kilometres. He used the prison library to provide background and research for the route. Speer reached Heidelberg on the day of his 50th birthday.

At this point, Speer continued, embarking on what Merlin Coverley referred to as “surely the longest, most sustained and most sophisticated imaginary walk ever undertaken”. Speer wanted to see how far he could walk around the world. The route was problematic, since the former Nazi did not want to pass through communist countries and he spent some time planning routes with Rudolph Hess. Speer ordered guidebooks and maps to support his obsession, and even describes what he might see in places he arrives – his diary mentions a demonstration in Peking on July 13th 1959. According to wikipedia, “He… passed through Asia by a southern route before entering Siberia, then crossed the Bering Strait and continued southwards”. Speer wrote “I would presumably be the first Central European to reach America on foot”.

Speer was released in 1966, after over a decade of walking. He had travelled over 30,000 kilometres and, the night before release, sent a telegram to a friend: “Please pick me up thirty-five kilometres south of Guadalajara, Mexico”. Sadly, the route chosen means Speer never reached Hampshire, the site of Hannan’s walk; although Speer did visit England several times after release, dying in London in 1991.

(The connection often made between the Leave campaign and racism has been rebutted in detail by Hannan, notably in an article written on the first anniversary of the vote)