“…far from being the aimless, empty-headed drifting of the casual stroller, Debord’s principle is nearer to a military strategy and has its roots not in earlier avant-garde experimentation, but in military tactics, where drifting is defined as ‘a calculated action determined by the absence of a proper locus.’ In this light, the dérive becomes a strategic device for reconnoitring the city, ‘a reconnaissance for the day when the city would be seized for real.’”

– from Psychogeography by Merlin Coverley

The English have done terrible things to psychogeography.

In England, psychogeography is most often considered as a literary technique. This bookish reinvention can be traced back to Iain Sinclair’s book Lights Out for the Territory. Sinclair drew lines across London, reinventing the city as a place of maverick philosophy. Subsequent works such as Merlin Coverley’s excellent study, Psychogeography, explore Sincliar as part of an English tradition of psychogeography avant la lettre, taking in visionaries such as Blake, Defoe and de Quincey.

It was this stream of thought that introduced me to psychogeography. I came to understand it though personalities like JG Ballard and the comic-book writer Alan Moore. My only knowledge of Situationism was through the use of slogans in punk or references in works like Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles. For the music press, Situationism’s most significant thinker was Malcolm McClaren, who used detournement and Debord as the theoretical structure for his ‘rock and roll swindle‘.

When I returned to university in the mid-noughties, I took a course on Marxism which introduced me to psychogeography’s other tradition, original yet younger: a revolutionary art movement based on the philosophy of Hegel and Marx, emerging from ultra-left politics. I was exposed to the uncompromising force of Debord’s thought and became aware of his rage, even against his own attempts to escape capitalism’s confines.

The most obvious trace the Situationists left were their slogans. As great as the core texts are, they are incredibly difficult compared to the slogans’ Zen simplicity. What better statement of anti-capitalist revolution than “Never work”? Arguably the most famous statement from May 68 was the graffiti ‘Sous la pave, la plage’: Under the paving stones the beach. It’s seen as a cute moment of utopianism, perfect for putting on T-shirts.

Debord was not seeking a beach. The slogan came from a violent time, as de Gaulle struggled to maintain control. That slogan ‘sous la vide, la plage’, urged the enrages of 1968 to pull up the paving stones, the implication being that they could be broken up and hurled at the authorities. Psychogeography was intended as part of this revolutionary struggle, reconnaissance for a coming urban war.

With his writings on recuperation, Debord was aware that whatever he did would, in time, be sold. Nothing is so chaotic that one cannot make cash from it: Banksy’s rebellion advertises his role as a fine artist; Grant Morrison satirises royalty yet is happy to take an OBE; Iain Sinclair, the saint of walkers, did an advert for Audi. And TV panellist Will Self started his Psychogeography column, bankrolled by the British Airways in-flight magazine. Self and Sinclair were eager to hawk psychogeography and their reputations for advertising. Debord always knew his ideas would be stolen, turned into fuel for Capital. But that makes what has happened no less tawdry, shameful and treacherous.

There has long been a tension between French and English psychogeography. When Debord visited the English Situationists he was shocked at their shabbiness and lack of preparation. Later, punk stripped away Situationism’s complex political theorising to leave a simpler call to action. From early on it was obvious that Debord’s ideas, as powerful as they were, would be diluted and recuperated.

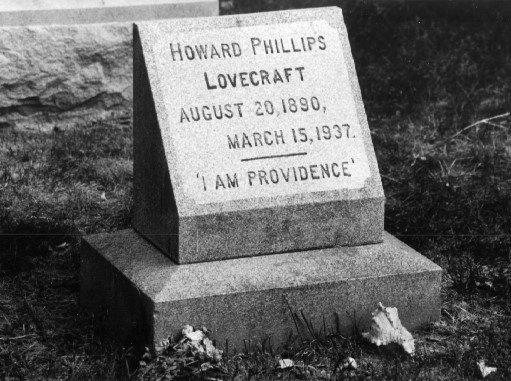

Sometimes it feels like a tragedy that this English tradition has the same name as Debord’s discipline. Both are important, but English psychogeography seems a quivering, obedient thing in comparison to Debord’s spitting fury. This is a man so uncompromising that he bound his first book in sandpaper to destroy anything it was shelved besides. It’s a long way from the lettrists. It’s a long way from revolution. Psychogeography has become safe and cosy, no threat to anyone.

I’m not interested in car salesman Sinclair and his sesquipedilian prose. I want short, punchy phrases, ones that bruise. We live on the home front of a global war, deafened and blinded by the propaganda of marketing which leads to, say, a famous walker hawking himself for petrol-gulping car companies.

At the same time, the world is stolen from us. Take Jubilee square: once a derelict gap in the North Laine, with little in its favour other than some pleasant graffiti. The square in front of the library should be one of Brighton’s main town squares but it has no buskers, no community, just controlled PFI-funded private property. Sometimes the square is rented to corporations for advertising, or even the project of filling the space with a huge mat of fake grass. And we are supposed to be grateful.

Maybe it’s time to tear up the paving of Jubilee square and hurl the broken stones through the windows of the library. I’d like to see every sign that bicycles can’t be chained to a railing obscured. By bicycles welded in place over the fucking sign. I’d like to see Churchill Square and Jubilee Square reclaimed for the town, places to play hopscotch without being chased away by security guards. We need a more aggressive psychogeography. We need to beat the bounds, mark out what is ours.

If psychogeography is not revolutionary, it is dead. And if psychogeography is revolutionary it brings conflict. By all means, wander the city between greasy spoon cafes, chatting with artists, and recording your explorations for TV cameras. But remember that what you’re doing should be reconnaisance too. Psychogeography is about recapturing occupied territory.

Fuck psychogeography – it cannot exist without revolution. Guy Debord was a strategist. It’s about understanding how Paris was redesigned to allow the army to put down insurrections. It’s about breaking down the illusions of the spectacle in the hope of being free. It’s about territory.