I spent much of January in the pandemic doldrums. I’d been planning to do more with my free time, but just can’t get enthusiastic about risking covid. But, at the same time, I’m spending too much time on my own, and need to make some effort to explore my new environment. It’s hard to know what to do. The combination of virus and political chaos sets a depressing backdrop.

But, while things are bleak, I’m trying to make the most of it. I had visits from Katharine and Kaylee, the latter bringing along her DJ equipment. I was tempted to get a set of my own, but had to be honest with myself – I don’t know how I’d find time to use them. I also visited family back in the midlands, and made a day-trip to York to visit Justin.

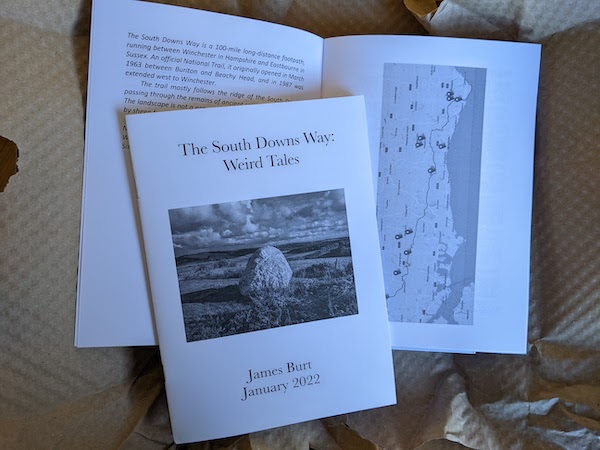

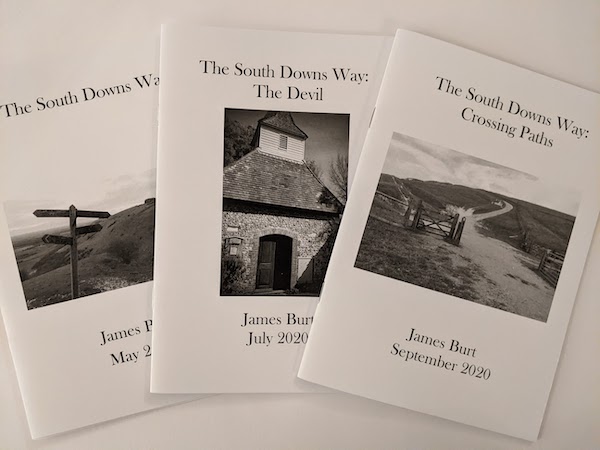

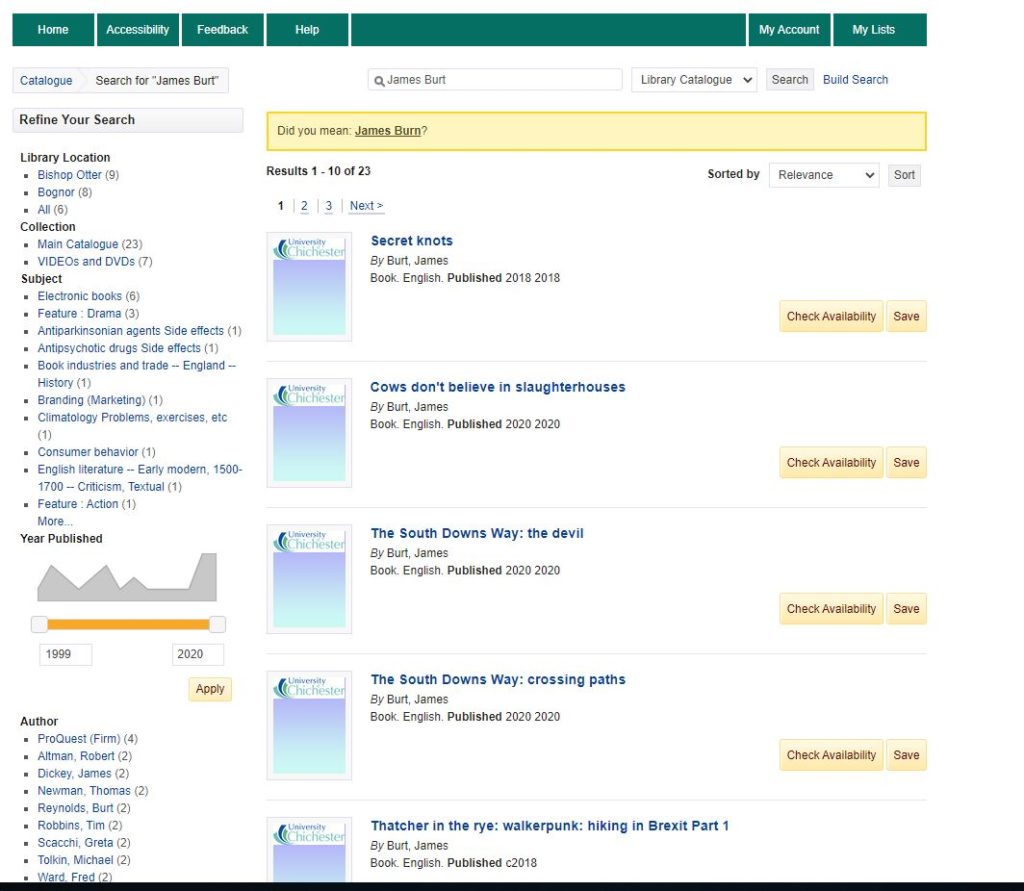

One of the things I wanted to do with 2022 was to put more writing out. This month I brought out a new zine of South Downs Way stories, Weird Tales. I also set up an etsy shop for my zines, something I should have done long ago. Putting the zines on sale is making me think about how to make my writing more appealing. This is feeding back into the writing of Volume 5 and, I think, making it stronger.

Another change for 2022 was reducing my daily walking commitment from 10,000 steps to 5,000. Despite that, I managed a total of 294,048 steps, a daily average of 9,485 – not that far off my old target. This was helped along by a few long hikes, and my highest total of 29,672 was a day out with the local Ramblers around Hebden Bridge. I got soaked, which serves me right for being complacent about Calder Valley weather. I didn’t manage much other exercise despite what I had promised myself. I must at least do my stretches.

It’s been a good month for TV. Snowpiercer and Ozark have both started new seasons – although Ozark suffers a little from spending too much time on the Byrde family and not enough time on Ruth. I’ve finally got hold of How to with John Wilson, and love the beautiful weirdness of Wilson’s New York. I came to Yellowjackets a little late, but it’s one of the best shows I’ve seen in years, and I binged the series in five days. The only film I saw was a rewatch of Midsommar.

I finished eight books this month. Last of the Hippies by CJ Stone was an interesting discussion of British counterculture, focussing on working class experience. Paint my name in Black and Gold described the early days of Sisters of Mercy and how Andy Taylor from Leeds was taken over by Andrew Eldritch. It was exhaustive in some aspects (Eldritch was partial to Fruit Shortcake biscuits), but I was sad not to hear any stories of the Sisters touring with Public Enemy. Also, Eldritch tried to get Werner Herzog to produce his album, although it faltered when Herzog suggested he and Eldritch go camping along some ley lines. Best book of the month was Olivia Yallop’s Break the Internet, which explored the world of influencers.

Like everyone else, I’ve been playing Wordle and enjoying the mix of luck and skill. I’ve also continued to waste time on Days Gone. It’s not a bad open world game, and I like the fact that it’s not entirely nihilistic. But sometimes it just feels like having a boring imaginary job.

And so we move into February… Let’s see what it brings…