I’m a little behind in posting about my adventures. In the middle of January, I went to the Chepstow Wassail Mari Lwyd in Wales. This annual event features morris dancing, a wassail, and what wikipedia describes as people “disguised as a horse”. This disguise involves a decorated horse’s skull and a sheet, along with a lower jaw that can snap at passers-by. I saw the event in the Rites and Rituals film and had to go. It was a good trip and the Mari Lwyds looked amazing.

Author: orbific

A Cheeky Walk: Ceci n’est pas une promenade artistique

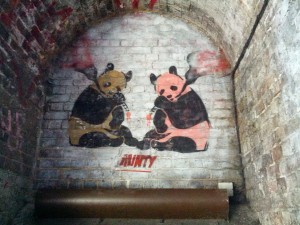

This Sunday’s Cheeky Walk was a shorter one, two miles starting at Brighton station then winding through the North Laine and Lanes to the seafront before finishing back at the Museum. A lot of the places visited were familiar but it’s amazing what else you notice when you’re stopping to take photos:

The morse code above the Albert’s side door, spelled out in spraycans, apparently reads ‘Wish You Were Here’

The Banksy on the building’s side is a reproduction, despite the perspex protection.

The North Laine has some amazing stencil and sticker art, as well as the Kensington Street Murals (which are currently under threat)

On the seafront, it was a warm Spring day, despite only being February. The guidfebook pointed out the public art, as well as leading us to the JAG gallery, which I’d never been inside before.

We finished the walk with a meal at La Choza and a tour of the museum. The shorter walk wasn’t as much fun as the longer ones, and we felt we could have managed a couple back-to-back. But it was good to get out and explore the town on what felt like the first day of Spring.

A Cheeky Walk: A Matter of Life and Death

I did my 3rd Cheeky walk of the year on January 25th but failed to get the photos up until now. It was another dry day and we did the Life & Death walk. This started with the Lewes Road cemeteries before taking us over the top of the race-course and then dropping us off in Kemptown.

While the second half of the walk was a little underwhelming, it was great to spend some time exploring the extra-mural cemetery.

The last picture shows the grave of Edward Bransfield, the first man to see Antarctica. According to Wikipedia: “During 2000 the Royal Mail issued a commemorative stamp in Bransfield’s honour, but as no likeness of him could be found, the stamp depicted instead RSS Bransfield, an Antarctic surveying vessel named after him.”

I don’t seem to have taken all that many pictures of the second half of the walk:

The book did promise us “the best view in Brighton” though and this was indeed pretty spectacular.

The Return of Not for the Faint-Hearted

Some years back now, Ellen de Vries and I started Not for the Faint-Hearted. It was intended as a one-off experimental writing workshop but was so much fun that it became a monthly event. It’s been on hiatus for a while but I brought it back last night for another session at the Skiff. We had 14 people, a mix of old faces and new, and it was as much fun as ever.

The aim of NFTFH is that we show the group a picture and they have three minutes to write a response – a story, poem or some dialogue. Then everyone has to read out something of what they’ve written. And you’re not allowed to apologise. What I like most is how funny and entertaining the pieces are – whether or not the people doing them consider themselves writers or not.

Next month’s event is on March 9th and tickets are now available. The pictures this month were:

32: Public space

San Francisco has the concept of Privately Owned Public Open Spaces – ‘parks’ built as part of new developments. This was set out in the 1985 Downtown Plan but it has been proposed that the requirement come to an end, with a payment in lieu of setting aside the increasingly rare space.

The existing parks are apparently little-used: “the locations are deliberately hidden to keep the public out. In consequence, the lack of usage enables a legitimate case to stop building public spaces.” The spaces are deliberately hard to find and therefore neglected. One ironic effect of this: “The tourism industry has turned this into a tour of “San Francisco’s secret spots” — tourists are entertained by on POPOS that locals are not even educated about.”

A guide to these parks has now been produced, enabling people to go to these public areas – to take lunch, to meet friends or just enjoy a calm space.

There is a similar contest between public and private space in Brighton. Two of the town’s main spaces, Churchill Square and Jubilee Square, are both privately operated. In Churchill Square there is a line in the pavement separating the wide private space from the narrow strip of public land. A sign on the library wall reads “No public events or performances without Owner’s written permission”. Jubilee Square has no buskers or people handing out leaflets. It is mostly left as empty space.

Slash/Night2

Way back in September, I teamed up with Muffy Hunter, Chris Parkinson, Mathilda and Kate to put on Slash/Night, a celebration of slash fiction. For me, this was more a night I wanted to attend than one I was particularly knowledgeable about. Putting on the event was hard work (particularly when Chris had to excuse himself for a film premiere) but it all went well and I was very pleased with the night we put on.

Slash is a hugely popular genre and probably has a larger following than literary fiction. Yet it is mostly ignored or even mocked. For me, one of the best things about the night was that for some fans it was the first time they’d been somewhere they could discuss this in person.

I’ve handed over the running of Slash/Night to Mathilda and she’s put on an amazing bill for Slash/Night2. We have the novelists Naomi Alderman and Julie Cohen reading. We have pre-internet slash. We have a talk from Muffy about her experiences. We have Welcome to Night Vale slash. We even have a creator reading slash written about their own creations.

The last event was funny and filthy and this one looks like being even better. Even better, I’m not organising, so I can just sit back and enjoy the night. You should come too.

31: Hypersigils

Psychogeography has probably become a literary form because written accounts are the simplest way of recording a walk; there were other options such as maps or art, with several examples of the latter provided by the work of Richard Long. This has led to the development of psychogeography as a literature rather than following other routes.

Another path that could have been taken is occultism. There is a thread taking in Arthur Machen; Alan Moore’s work on ceremonial magic and place, such as in From Hell; Alfred Watkins theory of ley lines; and the work of the London Psychogeographical Association which inspired Grant Morrison.

Grant Morrison’s book the Invisibles was written as a spell, a way of changing the world, what Morrison referred to as a hypersigil. In magic, a sigil is a symbol that represents the aims of a magician and is used to power and focus their intention. A hypersigil is a work of art that is designed to work as a sigil, drawing on the audience too. “The Invisibles was a six-year long sigil in the form of an occult adventure story which consumed and recreated my life during the period of its composition and execution”

Morrison identified himself with one of the book’s characters. During an interrogation sequence that spanned multiple issues, as this character was tortured, Morrison himself became dangerously ill, almost dying from MRSA-related septicaemia. These experiences were then themselves worked into the storyline; after recovering Morrison resolved to give the character an easier time from then on.

Psychogeography is a confusion of mingling disciplines, but some of the more interesting promises seem to have been neglected. What would it be like if psychogeography followed its occult influences and attempted to follow the line of magic. What if, rather than trying to craft art, psychogeography attempted to craft hypersigils, to produce changes rather than traces?

30: Situationist Disneyland

Writing about Ivan Chtcheglov’s Formulary for a New Urbanism, Merlin Coverley is somewhat underwhelmed. He says that “the details for establishing such an environment are absent here”, giving as an example lines such as “Everyone will, so to speak, live in their own personal ‘cathedrals.'”

Coverley is perhaps a little too harsh, because Chtcheglov does have some suggestion; the problem is that the ideas are not as radical as he tries to claim. The main proposal is a division of the city into zones. Chtcheglov writes that “The districts of this city could correspond to the whole spectrum of diverse feelings that one encounters by chance in everyday life.” He gives some examples:

“Bizarre Quarter — Happy Quarter (specially reserved for habitation) — Noble and Tragic Quarter (for good children) — Historical Quarter (museums, schools) — Useful Quarter (hospital, tool shops) — Sinister Quarter, etc. … The Sinister Quarter, for example, would be a good replacement for those ill-reputed neighbourhoods full of sordid dives and unsavoury characters that many peoples once possessed in their capitals”

A proposal to zone a city hardly seems radical, particularly when such things are carried out in most areas. These attempts to control creativity, to plan and organise it, have irritated some people, such as the artist Bill Drummond: “How dare someone tell me where the cultural quarter is? How dare anybody decide where culture can be found, or what it is, or how it can be safely packaged in a sanctioned part of the city”. Having a cultural quarter implies a restriction of creativity to a certain area. One suspects Drummond would not be a fan of Chtcheglov’s proposals.

Even worse, from a Situationist point of view, is the way in which Chtcheglov plans to support his imaginary project:

We know that the more a place is set apart for free play, the more it influences people’s behaviour and the greater is its force of attraction. This is demonstrated by the immense prestige of Monaco and Las Vegas… though they are mere gambling places. Our first experimental city would live largely off tolerated and controlled tourism.

While Debord was inspired by the idea of play, particularly in relation to Huizinga’s ideas, he was suspicious of ‘leisure’, seeing recreation as a way to keep workers participating in capitalism. The “tolerated and controlled tourism” that Chtcheglov suggests is indistinguishable from this. As charming as some of Chtcheglov’s visions are, the utopian city he suggests, his Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, is basically an urban Disneyland.

29: Psychogeography and Maps

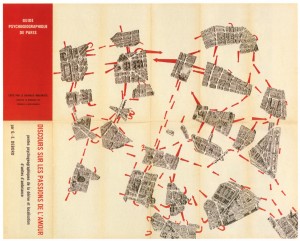

Given that the Situationists were a movement of artists they produced few iconic images. One that has emerged is Guy Debord’s Psychogeographic Guide of Paris, showing the city as a series of disconnected neighbourhoods with arrows showing the flow between them.

Psychogeography was, in part a mapping project. As Debord writes in Theory of the Derive:

With the aid of old maps, aerial photographs and experimental dérives, one can draw up hitherto lacking maps of influences, maps whose inevitable imprecision at this early stage is no worse than that of the earliest navigational charts. The only difference is that it is no longer a matter of precisely delineating stable continents, but of changing architecture and urbanism.

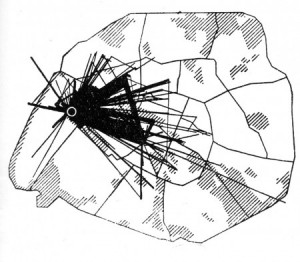

Debord was also inspired by a map produced by the French sociologist Paul-Henry Chombart de Lauwe, charting the movements made by a student over the space of a year, which shows ““the narrowness of the real Paris in which each individual lives”.

(This work is echoed by the news in 2012 that an algorithm produced by the University of Birmingham could predict where someone would be in 24 hours “even if it’s a major change from their usual routine”)

Maps in psychogeography has been neglected in favour of the derive, possible because a clearer method was developed for drifting, possibly because drifting requires less work. But even the Derive is linked to mapping, with the common methods being to draw arbitrary shapes on a map and take those as routes on the ground. Another technique, suggested by Debord, is to use a map of one place to navigate another: “A friend recently told me that he had just wandered through the Harz region of Germany while blindly following the directions of a map of London.”

The Situationist obsession with maps and territory uncovers a contradiction at the heart of the group. Merlin Coverley has quoted Simon Sadler: “Like the imperialist powers that they officially opposed, it was as if the situationists felt that the exploration of alien quarters (of the city rather than the globe) would advance civilisation”

28: The Perfect Guidebook

‘Proper travellers’ tend to sneer at the Lonely Planet guidebooks and, in particular, at people that follow them too carefully. Part of this is resentment at how they have produced a familiar environment in very different countries. The repetitive breakfast menus in vastly different countries have led to the creation of the Banana Pancake Trail. Wikipedia describes this trail as including Pushkar, Goa and Varanasi in India; as well as Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and even parts of China.

But there are things you need to know about a country before you get there, such as how to get around, what legal rights and cultural expectations surround travellers, and which places are best avoided. It’s also good to know the local scams – while getting involved in a jewellery investment in a foreign country is foolhardy, there are elegant cons that easily capture the jet-lagged and unwary.

I would never have gone to India without a guidebook but my favourite moments have been places that were a little off that trail: cities like Gwalior or Lucknow that are almost completely ignored by tourists; chai shacks at the sides of busy roads. And I’ve done better with hotels by turning up in a new city and seeing what is available. I could probably discard the guidebook and have a more interesting time without it.

Perhaps the guidebooks shouldn’t list establishments but rather give you just enough information about a place before you arrive: what you should see there, places to start looking for hotels if you can’t find somewhere near the station; where to move on to if you can’t find anywhere to settle. A guide that is part of the trip rather than trying to define it. One that persuades you to go and gives you the confidence to see what happens.