I picked up a cheap kindle copy of Gurnaik Johal’s novel, Saraswati, and have it cued up to read after You Dreamed of Empires. The Guardian review is lukewarm, but attracted me with this section:

…his first novel is a representative example of a ubiquitous 21st-century genre. That genre lacks a name – in 2012, Douglas Coupland proposed “translit”… its features are all too recognisable. These novels contain multiple narratives, each set in a different country if not continent, often in a different century. Although long by modern standards, they are packed – with events, themes, facts. They address themselves to the big questions of the day, not by the traditional means of examining urban society but through a kind of bourgeois exotic. The characters are paleontologists, mixed media artists, every flavour of activist, but never dentists or electricians. The settings are often remote: tropical islands or frigid deserts.

The reader puts these novels together, like jigsaw puzzles. This term won’t catch on either, but one could call them “connection novels”; not in the Forsterian sense of human hearts, but rather the ecological, cultural and financial structures that link the globe… Not coincidentally, they owe a lot to science fiction.

The connection novel sounds similar to the systems novel (Keshava Guha’s review directly invokes DeLillo, Pynchon, Richard Powers and David Mitchell).

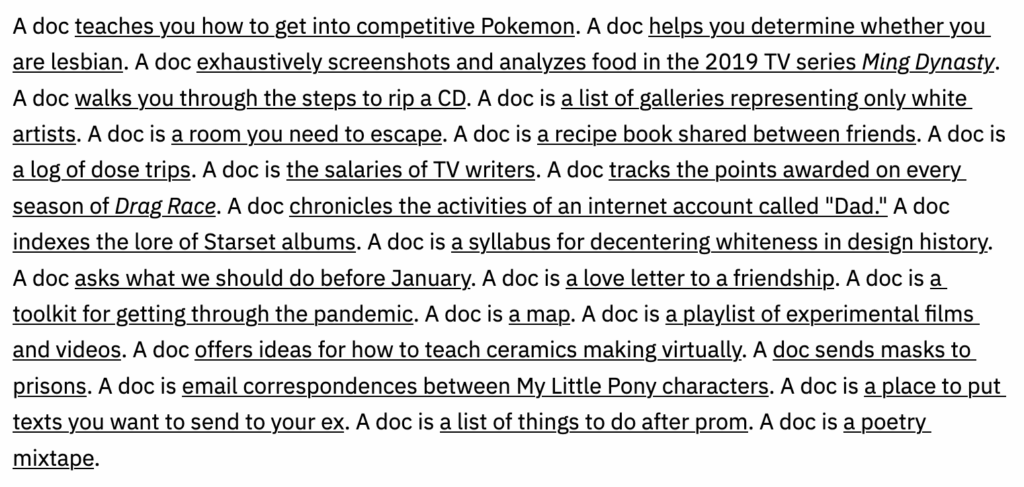

One of the thing I’m looking forward to with Saraswati is seeing a way of constructing a novel with smaller jigsaw pieces. I’ve always wanted to build something larger from the sort of microfictions that I write. The description of the ‘connection novel’ above sounds like a way forward.