Later today, I’m giving a talk at Brighton’s Sunday Assemly about Psychogeography. I originally spoke on this topic there back in 2018. As part of the preparation, I wrote out this simple introduction to Psychogeography. The exercise at the start is an adaption of one in A Road of One’s Own by Robert MacFarlane.

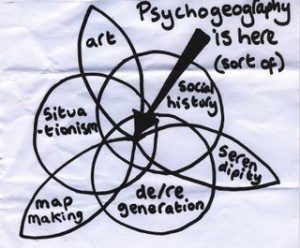

Psychogeography is about finding new ways to explore familiar spaces. It’s a fancy name for a playing with an environment. There are various definitions, but the best way to approach it is through an example:

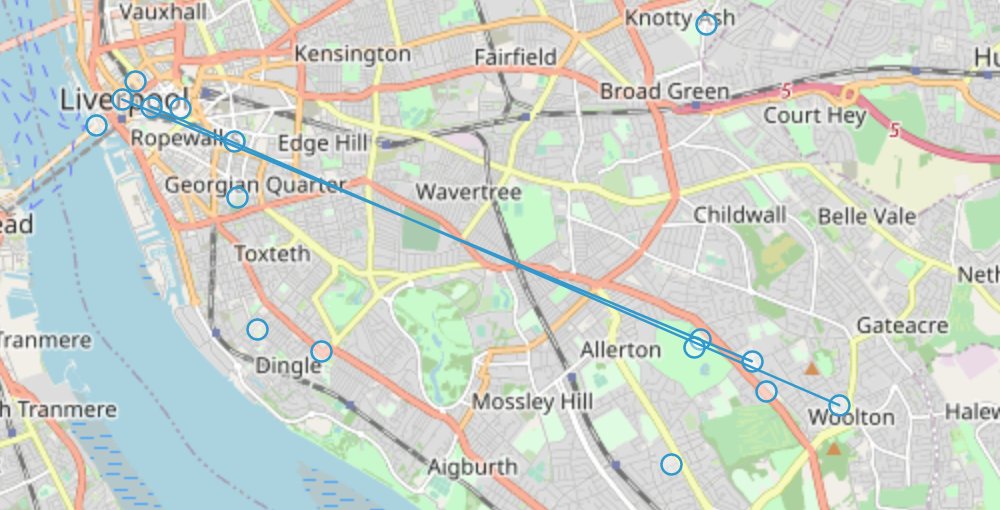

Take a map of the area where you live. Place a glass upside-down on the map and draw around the edge. Now, go outside with the map, and try to walk as close as you can to the edge of this circle. Make a note of the things you see, staying alert for novelty or strangeness. You could take photos, scribble notes, use voice memos, post to social media, or just remember what you see. At the end of the walk, review what you have produced.

It’s a simple task, and shouldn’t take long, depending on the scale of the map used. The important thing is trying. There is a difference between reading about something and doing it.

What you get from the experience will depend on where you live. In a city centre, you’ll be dragged away from the usual thoroughfares, and find yourself cutting through your regular lines of travel. In the countryside, paths will be sparser, and attempting anywhere near the circle’s edge will make you very aware of private land. In suburbia, the roads are unlikely to co-operate with making a circle at all, making you even more aware of how your routes are restricted.

What about the places you’re passing through? What do you see/hear/smell on this expedition? What have you not previously noticed about a familiar areas? For me, I tend to pick up on things like graffiti, the little ways people interact with places they don’t own. For other people it’s architecture, or advertisements. The important thing is being open to what the environment communicates.

You can explore different ways of documenting the experience: a set of photos or a simple social media post (“I saw this!”) through to a zine or a poem. Or, if this feels too much like homework, just look back on whatever you did to record the experience. It doesn’t need to be shared if you don’t want to.

This is a simplest example of psychogeography. If you want, you can stop reading anything else about the subject, confident you know enough to explore the idea. You can decide for yourself how to expand this. Rather than walking, you could explore an area through bus routes. If mobility means you can’t leave the house, then you can explore through Google Maps, or giving a friend instructions for the journey and asking them to report back. You could pick random routes through an area. You can find different ways to record the walks – maybe pick words that you see and write them down.

The important thing is attempt the experiment. Then you’ve done some psychogeography and, if you want, you can call yourself a psychogeographer. There’s little more to it than that.