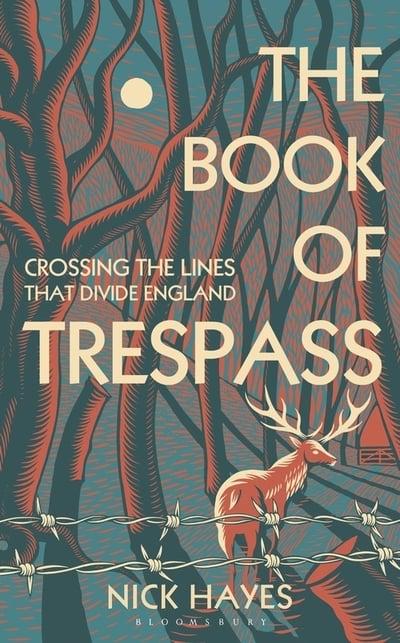

I had to get the Book of Trespass after reading a promotional interview with author Nick Hayes. It was fascinating and I was almost frustrated at how many other subjects it made me want to read about, such as the Harrying of the North or the King of the Gypsies.

The book is a history of trespass in the UK, along with Hayes’ accounts of his own incursions. Private land is something taken for granted in this country; so much so that, as Hayes describes, being told we’re trespassing has a near-magical effect, a speech act producing physical responses in the listener. By tracing out the history of land, Hayes shows us that this ownership is an invention. This history of property is embedded so deeply in our language that it is almost invisible. Hayes explains that that the word ‘forest’ derived from the latin word ‘foris’ meaning outside, alluding to how the forests were royal hunting grounds, outside the normal law of the land.

I’m not sure how well the accounts of trespassing sat with the scholarship. It felt, a little, like the book was trying to fit into the “man-has-an-adventure” genre. It’s not to say that the personal accounts weren’t fascinating, just that it felt like two books running alongside each other.

The book shows how many of the ills of the world are played out in the land, particularly in English land. While some on the right are trying to make the connection between British manor houses and slavery controversial, Hayes shows clearly that ownership of British land is still defined by the atrocities committed years ago. We are told that the crimes and lawbreaking of the past should be forgotten, while upholding the law in the present day; told that an arbitrary removal of this current property is an injustice. Looked at from one angle, this becomes odd and arbitrary. Why should land obtained by past theft be sacrosanct now?

While Hayes can see the importance of laws like the right to roam, he points out that such things also reinforce the idea that there is a set of land rightfully lost to us. Having read this book, it’s hard to see how Britain can really be a democracy when its property laws are so unfair; but the book also opens up possibilities.

One of the characters in the book is Richard Drax, MP for South Dorset since 2010. Drax owns over 13,000 acres of land in Dorset, among other holdings. Drax has strongly dismissed any criticism of his family and his fortune being linked to the slave trade.

You will have seen Drax’s estate if you’ve driven along the A31. It has one of the longest brick walls in Europe, and includes the striking stag gate. In 2013, Drax voted to increase curbs on immigration, saying “I believe, as do many of my constituents, that this country is full”

As Hayes says (p371), “If England is full, it is full of space. And the walls that hide that”