One my favourite records is Secret House Against the World, a 2005 release from rapper Buck 65. It’s a peculiar hip-hop record, with tales of roads trips and defeat. I’d not heard anything like it and fell in love with the songs – particularly the mournful track Blood of a Young Wolf

Buck 65 had a prolific career until 2015 when he suddenly went on hiatus. Every so often, I’d look online to see if he had re-emerged again, but it looked like he had retired from music. I couldn’t understand how this constant flow of creativity had just stopped. And then I learned on twitter that Buck 65 was returning with a new album and had started a substack.

Buck 65 is a great writer, and tells some great stories on his blog (check out Play Ball from May, where he talks about his renewed focus). It’s obvious that he has wrestled with his career and what he wants to produce. He’s talked about how uncomfortable he is with some of his ‘emo’ material, and how much he loves his earlier, more traditional hip-hop records. While it was that emotional material that made me love him as an artist, I’m equally drawn by the passion and focus he brings to his new work.

On his mailing list he has spoken about a secret Instagram project that will never be released, where he cuts up drums for a small group of connoisseurs. He’s excited about showing off his old material. I’ve since discovered a rich seam of early work on collaborations on Bandcamp, including the Laundromat Boogie record which came out in 2014 alongside his pre-hiatus release Neverlove. I’d not heard Laundromat Boogie until this year, but it’s a fun and jubilant concept album about cleaning clothes.

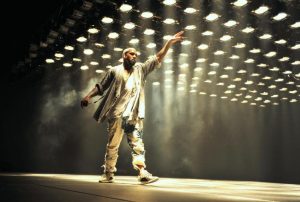

The new release is King of Drums. When this was released, Buck 65 performed what he said was going to be his last live show. I remember seeing him years before in Brighton’s Haunt many years ago. I was disappointed to see come on stage with just a laptop and a microphone. But then he spent the set telling us the story of his life, and how the recent record came to be, and it was one of the best shows I’ve seen.

I love Buck 65, for mournful songs like Blood of a Young Wolf, inspiring ones like Craftsmanship, and uplifting ones like Indestructible Sam. Buck 65 wants to be a very different artist to the one I was first drawn to, but I am enjoying the journey that the new work sets out on.