That was a very strange April – meaning some quite perfunctory monthnotes.

I am grateful every day for how easy my life is compared to a lot of people right now. I have a stable job I can do from home and a flat to myself. But life is still hard: I feel constantly anxious about the impact of the pandemic on my friends and community, and sleep is difficult. I wake very early most days, but this week I’ve been forcing myself to stay in bed till 5:30am which is helping.

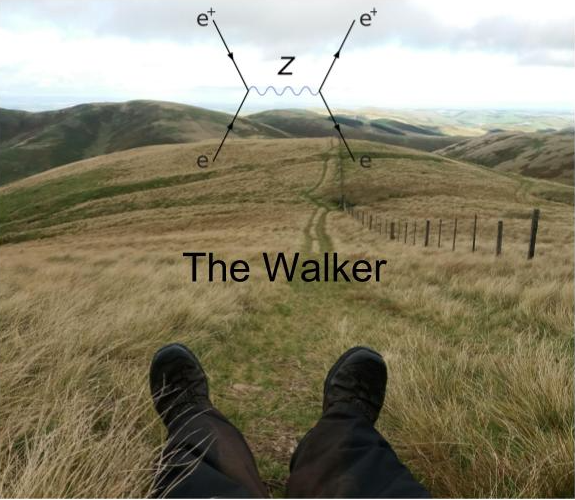

Walking has been a consistent 10,000 steps of daily exercise, with rare errands adding a few thousand steps. My total for April was 323,007 (200K less than in March), with my highest being 17,804 steps on the 3rd. My lowest was 10145, 30 more than my lowest in March, but I will ratchet the steps up for that. I go out early most days, when it is quiet, but the morning walk still feels stressful. Brighton is just too densely populated for social distancing to work easily. Sometimes I think I should just stop taking my daily walk, and exercise indoors; but I think that would leave me feeling more burned out and lethargic.

A couple of mornings I’ve taken a dip in the sea, which has left me feeling awake and alive, but most days it’s hard to summon the intention to go swimming.

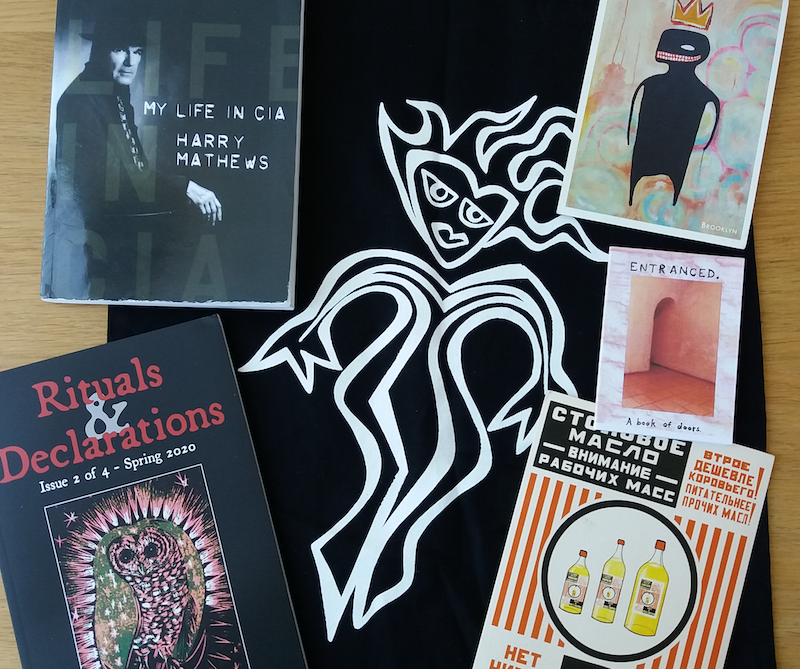

I finished 11 books in January, and just 2 last month – my concentration is not good. One of the books was a short one about Kurt Cobain, the other one of Mick Herron’s Slough House Spy Novels.

I didn’t watch any movies last month – my concentration is as bad at watching things as reading things. I’ve watched bits of a few series – Westworld has been mostly annoying, Devs started well and wore out its welcome. Netflix’s Sex Education (a recommendation from Rosy) was the only thing I enjoyed.

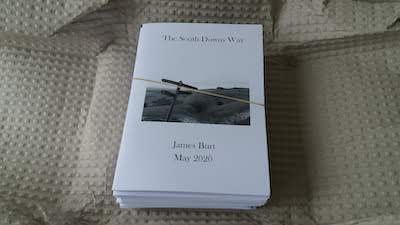

Above everything, writing has been rewarding. I’ve been running remote Not for the Faint-Hearted Sessions, and attending Naomi Wood’s workshops. I also published a new zine, the first part of my South Downs Way project. And today I’ll be working on a new spoken word piece for Zoom.

I read a blog recently where the author suggested the topic of “looking back at my 2020 resolutions and laughing/crying“. I had a read of my new year’s post:

No resolutions for 2020. Instead, I am planning to do less, making space for new things to enter my life. I am going to try reading more fiction, but that doesn’t require a programme or any goals.

I’ve found lots of space in my life, so I am winning at my new year’s resolution. I also re-read another post from January about the Pastoral Post-Apocalypse: “A world of fast fashion and cheap global air travel is coming to an end“. I hadn’t expected that to be so sudden.

We are in uncertain times. The days drag and the weeks fly by. But every day I am grateful for what I have. I miss people and sharing food and parties, but I’m happy enough for now.