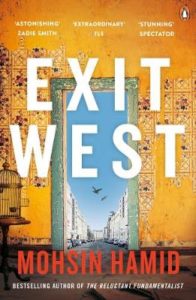

Exit West was a book-club choice, which I probably wouldn’t have read otherwise. It tells the story of two young lovers, Saeed and Nadia, who meet at an evening class. Nadia wears conservative dress “so men don’t fuck with me”, but enjoys riding a motorbike and smoking dope.

Exit West was a book-club choice, which I probably wouldn’t have read otherwise. It tells the story of two young lovers, Saeed and Nadia, who meet at an evening class. Nadia wears conservative dress “so men don’t fuck with me”, but enjoys riding a motorbike and smoking dope.

They live in an un-named city and, just after they get together, civil war breaks out. Their lives become incredibly dangerous. They are under curfew and become dependent upon technology: “without their mobile phones and access to the internet there was no ready way for them to re-establish contact”

The book was disturbing, making me think about the ties that bind us together. I became acutely aware that, should the Internet or phone system fail, I would have no means of getting news about my family, who live 200 miles away. The book is an incredibly empathic portrayal of displacement and the refugee experience (as Hamid writes, “we are all migrants through time”).

Deprived of the portals to each other and to the world provided by their mobile phones, and confined to their apartments by the night-time curfew, Nadia and Saeed, and countless others, felt marooned and alone

I was also surprised at a fantastic turn the book takes. One of the great things about book clubs is reading a book you know nothing about. It certainly wasn’t the book I expected it to be.

I finished the book at the start of March, and couldn’t stop thinking about it. Then the coronavirus pandemic arrived and overturned my world. I’m not saying that the experieces of Saeed and Nadia are comparable to my current experience, but I’ve been reminded how fragile daily life actually is, and how it can be overturned.

A recent article by Oliver Burkeman, “Focus on the things you can control” referred to a 1939 sermon by CS Lewis:

It wasn’t the case, he pointed out, that the outbreak of war had rendered human life suddenly fragile; rather, it was that people were suddenly realising it always had been. “The war creates no absolutely new situation,” Lewis said. “It simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it. Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice… We are mistaken when we compare war with ‘normal life’. Life has never been normal.”

Moments from Hamid’s book keep coming back to me:

when the government instituted a policy that no one person could buy more than a certain amount per day, Nadia, like many others, was both panicked and relieved.

Back when I read this book, such an experience was foreign to me. I’d yet to experience the anxiety of empty supermarket shelves. This book was terrifying and unsettling, and I’m shocked at how quickly my connections with the characters have deepened.

the apocalypse appeared to have arrived and yet it was not apocalyptic, which is to say that while the changes were jarring they were not the end, and life went on, and people found things to do and ways to be and people to be with, and plausible desirable futures began to emerge, unimaginable previously, but not unimaginable now, and the result was something not unlike relief.

Infinite Detail touches on this too – the notion of reconnecting in times of extreme disconnection, with a thread that balances between danger and celebration. Perhaps it’s not that we need the opportunity to reconnect with what we take for granted, but that we need the reality of risk to fully appreciate the *bravado* of extraordinary acts. To reorient ourselves, we must do uncomfortable things, and so much the better if this discomfort is for good, rather than evil…