In his book Our Pet Queen, writer John Higgs claims that Britain has two monarchs. One is Elizabeth Windsor; the other is King Arthur Uther Pendragon. In comparison with Elizabeth, King Arthur is “more likely to sleep in a ditch, drink cider until he pukes and set fire to people for a laugh”, but is “recognized as a King because his followers don’t know anyone who would make a better king”.

King Arthur was born John Timothy Rothwell in 1954 and spent time as a soldier and a biker. After reading a book on the mythical King Arthur, he spotted certain similarities and decided that he was Arthur reincarnated. He changed his name and was proclaimed King by several Druidic orders.

According to Higgs, King Arthur knows how mad this is, but he is also determined to live up to the ideal of King Arthur. He does not work or take benefits: “[King Arthur] can only eat and drink if people value him enough to feed him. His stout frame is, therefore, a source of some pride. Together with his long white hair and beard, it is hard to deny that this ex-soldier and biker has come to look an awful lot like a king.”

(Higgs also tells an excellent story about how King Arthur Pendragon found Excalibur, but I’m not going to regurgitate the book. My friend Michael Parker has also found Excalibur. I texted him while I was writing this piece to ask if he’d met King Arthur. Mike texted back to say that he had: “I told him that I had ‘an’ Excalibur, and he said then that I am ‘an’ Arthur”)

As a King, Arthur Pendragon took his first stand against the long-running exclusion zone against Stonehenge. He continues to participate in direct action with his followers, the Loyal Arthurian Warband and has accumulated a series of honorary titles.

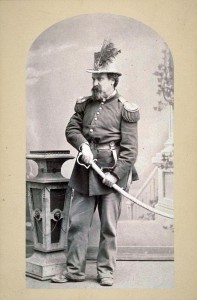

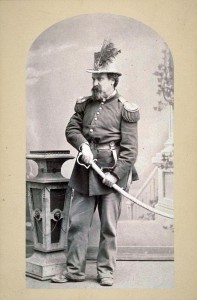

King Arthur Pendragon is reminiscent of another figure, the Discordian Saint, Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico. Norton declared himself Emperor in San Francisco in 1859, on nothing but his own authority. Despite that, his 21-year reign is generally seen as a good thing. Norton I is said to have dispersed anti-Chinese riots, released his own currency and was fed by the city’s restaurants. When arrested for a mental disorder there was uproar, with the town’s citizens demanding his release. The police chief apologised when the Emperor was released: “he had shed no blood; robbed no one; and despoiled no country; which is more than can be said of his fellows in that line.”

When Norton died in 1880, the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle declared “Le Roi est Mort”. At first, a pauper’s funeral was planned but his citizens demanded something greater. On January 10th 1880, the body of Emperor Norton I was paraded past 10,000 people with a funeral cortège 2 miles long.

King Arthur Pendragon and Emperor Norton draw attention to something important about power and legitimacy. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland has existed only since 1801; governments have come and gone. While they may not also be what we would choose, we can choose our ideals and leaders to an extent – but this does come with a responsibility. As King Arthur Pendragon says on his website: “Arthur is what Arthur does and I will be judged solely by my accomplishments.”